Having not played a video game for fifteen months, I vowed that, over Christmas, I’d do so. I only just found the time.

Fortunately, I chanced into something good and unexpected. Homesick is a short story told in game form. You have no weapons, there is nothing to frag: if anything, you revive life. You explore your environment, you change it. You solve puzzles, you learn, you enjoy what you see.

You wake up, alone, in a strange bed in an abandoned building, and your task is to leave the building. Obviously, it’s not quite as simple as that, otherwise opening the front door and walking out would make an unusually short and uninteresting game. Having said that, this game is short: investigating the puzzles and working through the various stages of the game will take most people only a couple of hours or so (it took me four, but then I’m dim in game playing terms).

It’s a short story of a video game, like a scene in a big commercial game. But it’s a rewarding experience.

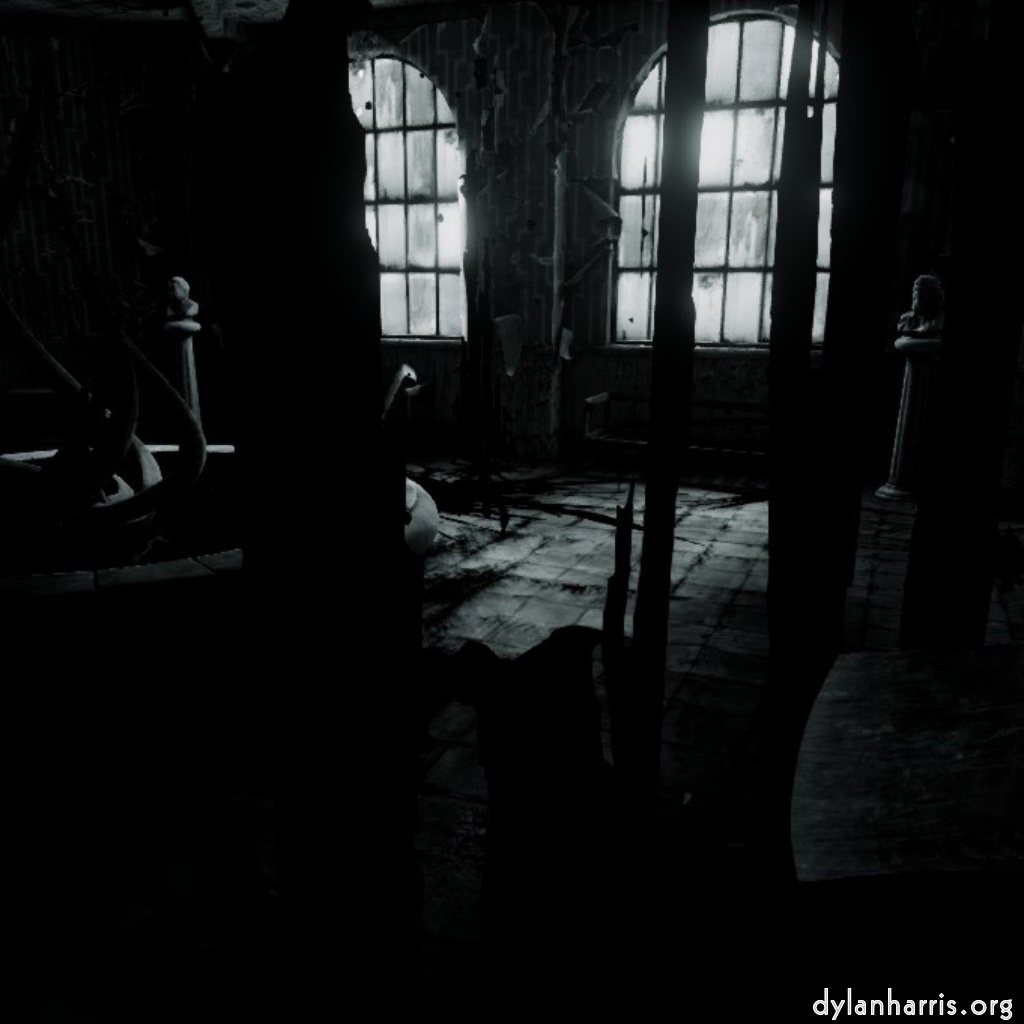

You wake up in a beautiful high spring morning, in a bright light derelict building, on an abandoned bed in an abandoned room surrounded by abandoned books and abandoned things. You potter about the place, opening things here, putting things there, realising you can’t read. When you have worked through this stage, you return to the bed, fall asleep, and the dark nightmares start, the nightmares with rising black fear and the need to escape. Or is this running through the dark stress really a nightmare? What if your black dream can change your world? Are you really asleep?

All the glare of the spring day and the delusions of the black night actually make perfectly good sense in storytelling terms—once you’ve got to the reveal. Follow the story, return to the unread, and you’ll understand.

I don’t want to say too much for fear of spoiling, but I will say three things.

- We’re in classic short story territory: there’s not much there, and what there is moves the story forward—with one rather fun exception. Play the piano, folks. You don’t need to, but you do. The reward’s nothing, the playing’s a pleasure.

- I don’t think I’m giving away too much if I say that, at the beginning, you can’t read, but you learn as you journey through the building. The key tool to help you do so are reading blocks: the traditional toddler’s alphabet cubes. The mechanism to use these blocks was not obvious. There were no hints on how to work them, and there should have been. This is a core part of the game, and it’s not the place to frustrate players with an unexplained novel U/I element. And once you’ve sussed the mechanism, do you use it again? Does it play any further role in the game? No, of course not. This U/I was not thought through. Mind you, I’ll give Homesick, this kind of bad U/I is all over the gaming world: I recently spent 20 minutes with another game trying to work out how the **** I was meant to achieve an obvious goal. Those plonker designers had not properly documented their keyboard interface. People, here’s a simple principle of text: don’t create acronyms without writing them out in full at least once (not a Homesick error).

- At the very end of the game, you can say the protagonist escapes his prison, but I read it that he dies (oh, and if he’s a she, then she’s got a very masculine sigh), that his death was a relief. I think it could have been worked out a little better; the first time I saw the blinding sky cliché, it was clever, but now…. Still, as endings go, I’ve seen much worse.

I particularly like the sparing use of colour. I really like the sparing chamber music. I particularly like the contrast of the cornflowers. I really dislike the non–contrast between the sound of me playing that piano and a wet dog jumping on the keyboard.

Overall, pretty good, a great way to spend a couple of hours.